Bone Health and Disorders Related to Bone Metabolism

Posted on February 1, 2024 • 13 minutes • 2728 words • Other languages: Deutsch, Русский

Table of contents

Fundamental Aspects of Bone Function

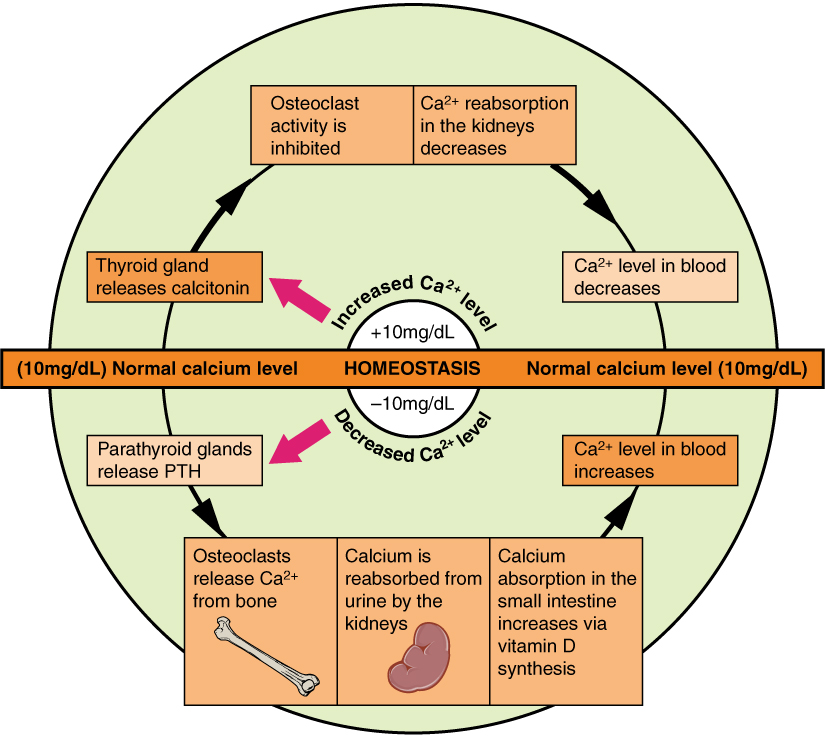

The dynamic nature of bone is characterized by ongoing cycles of bone breakdown by osteoclasts and bone formation by osteoblasts within specific bone remodelling compartments. Annually, approximately 10% of an adult’s bone mass undergoes this remodelling, which is crucial for both preserving bone strength and managing the body’s calcium levels.

| Calcium homeostasis and bone formation / resorption |

|---|

|

This remodelling process is a balanced sequence where bone resorption precedes bone formation. The regulation of osteoclastic activity, and thereby bone remodelling, is influenced by various systemic hormones and inflammatory substances, which operate through the synthesis of both bone-resorbing RANK‐ligand (RANKL) and bone-protecting osteoprotegerin by bone cells like osteocytes and osteoblasts. Discoveries in the regulatory mechanisms of osteoblasts are advancing, highlighting the significance of the Wnt signaling pathway and its inhibitors, such as sclerostin, which hold potential for developing new treatment strategies.

Understanding Osteoporosis

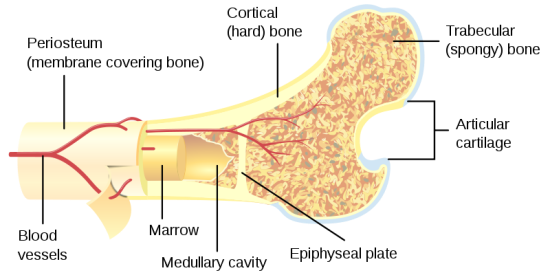

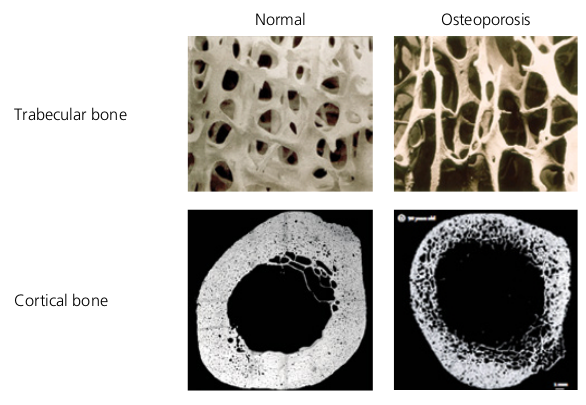

Osteoporosis represents a widespread condition affecting the skeletal system, marked by reduced bone density and a deterioration in bone structure. This leads to a significantly increased likelihood of fractures due to fragility. The condition becomes more prevalent with advancing age and certain medical conditions. Osteoporosis often develops due to an accelerated rate of bone remodelling where the balance tips towards more bone resorption than formation, especially under long-term glucocorticoid treatment. Early indicators include the weakening and perforation of trabecular bone, particularly noticeable in women during the early years following menopause, and a gradual increase in cortical bone porosity in both genders as they age.

| Ttrabecular (spongy) vs. cortical (hard) bone |

|---|

|

Bone Mineral Density (BMD) assessments, conducted through dual X‐ray absorptiometry (DXA) at critical sites like the femoral neck, total hip, or lumbar spine, are key in diagnosing osteoporosis. A T‐score of –2.5 or lower, indicating a deviation of 2.5 standard deviations below the young adult average, is the World Health Organization’s criterion for osteoporosis diagnosis in post-menopausal women and men over the age of 50. For children and young adults whose bones are still developing, BMD should be evaluated against the average for their age and sex, known as the Z-score.

| Normal and osteoporotic bones |

|---|

|

It is estimated that half of all women and one in five men will experience an osteoporosis-related fracture by age 90. In older populations, such as women over 75 years, any fragility fracture should be considered a consequence of osteoporosis unless a pathological cause (like metastatic disease) is ruled out. In the UK, the annual costs for managing new fractures are around £3.2 billion, which escalates to about £10 billion when considering the impact on quality of life.

Evaluating Osteoporosis

A significant proportion of fractures related to fragility are linked to aging, but in many cases, especially up to 40% in women and 60% in men, there’s an identifiable underlying condition (secondary osteoporosis):

- Thyrotoxicosis

- Primary hyperparathyroidism

- Cushing’s syndrome

- Hypogonadism including anorexia nervosa

- Diabetes (types 1 and 2)

- Malabsorption syndrome, e.g. coeliac disease, partial gastrectomy

- Inflammatory colitis

- Liver disease, e.g. primary biliary cirrhosis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

It’s crucial to conduct thorough investigations, particularly in cases where clinical suspicion is high. Those with a history of fractures from low-impact trauma or who display lower-than-expected Bone Mineral Density (BMD) for their age group warrant detailed examination. A comprehensive clinical history and a limited set of tests can help rule out common causes or other conditions, such as myeloma.

The presence of a previous fracture from a low-impact event is a significant indicator of risk. Often, prior spinal fractures may go unnoticed without specific spinal imaging. Low-radiation imaging techniques, such as vertebral morphometry using DXA machines, are now increasingly used for high-risk groups as part of standard evaluations. While DXA scans are generally reliable for measuring BMD, those interpreting the results should be mindful of potential technical errors and limitations. Other methods, like quantitative ultrasound, show promise in predicting osteoporotic fractures but there’s still uncertainty about the appropriate thresholds for intervention and their effectiveness in monitoring treatment responses.

The decision to perform a DXA scan or start treatment increasingly relies on assessing the absolute risk of fractures, as suggested by NICE. In the UK, two tools for assessing fracture risk are available: QFracture and FRAX, with FRAX having the added benefit of incorporating BMD data. The FRAX tool (available at www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX) calculates the likelihood of major osteoporotic fractures (such as clinical vertebral, hip, wrist, or proximal humerus fractures) or a hip fracture occurring within the next decade, based on several clinical risk factors, with or without incorporating femoral neck BMD. For optimal risk assessment, BMD measurements are most effective when directed at individuals whose fracture risk hovers around or exceeds the threshold for intervention. This approach is supported by NICE and is integrated into FRAX through guidelines from the National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (www.shef.ac.uk/NOGG).

Minimizing the Risk of Fractures

The primary aim in managing osteoporosis is to decrease the likelihood of future fractures. This is achieved through educating patients, preventing falls, adopting healthier lifestyle choices, and employing medication-based treatments. In situations where DXA scanning is not readily available, it might be sensible to commence treatment for individuals at high risk of osteoporosis without a DXA scan. This includes older adults who have sustained fractures typical of osteoporosis or those requiring high doses of glucocorticoids. An important aspect to consider in cases of secondary osteoporosis is that addressing the root cause can often lead to a significant recovery of bone density. Organizations like the National Osteoporosis Society (accessible at www.nos.org.uk) offer valuable resources and support for both patients and their caregivers.

Medications for Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis treatment primarily involves two categories of medications: antiresorptive and anabolic agents , with new drugs in both categories expected in the near future. Current medications are known to decrease the risk of spinal fractures by 40–70%, hip fractures by 40%, and other types of non-spinal fractures by 20–30%. It’s important to view lifestyle modifications and supplements such as calcium and vitamin D as complementary to main osteoporosis treatments.

| Optimizing peak bone mass and reducing bone loss |

|---|

| 1. Exercise needs to be regular and weight bearing (such as walking or aerobics); excessive exercise may lead to bone loss |

| 2. Dietary calcium may be important, especially during growth |

| 3. Avoidance of smoking and excessive alcohol consumption |

Supplementing vitamin D , either alone or in combination with calcium, can be especially beneficial for frail, elderly patients who are confined indoors or living in care facilities. Before starting other treatments, particularly intravenous bisphosphonates or subcutaneous denosumab, it’s crucial to correct hypocalcemia with sufficient calcium and vitamin D intake. Treatment adherence can be a challenge for some patients, so factors like patient preference and the simplicity of the treatment regimen should be considered when selecting a therapy.

Treatments That Inhibit Bone Resorption

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

HRT is particularly beneficial for women under 50 who experience early menopause, as well as in the initial years after menopause. It helps in preventing bone loss and alleviating menopausal symptoms. Estrogen-only HRT is perceived as having a safer profile compared to combined estrogen-progestogen therapy, though it’s mainly recommended for women who have had a hysterectomy . Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) function as estrogen activators in bone and lipid metabolism, while not stimulating breast and endometrial tissues. When used alone, SERMs may worsen menopausal vasomotor symptoms . However, new formulations combining SERMs and estrogens are being developed to address vasomotor symptoms, vaginal atrophy , and to prevent postmenopausal osteoporosis. It’s important to note that all oral estrogen-like treatments might slightly increase the risk of thromboembolic events. Additionally, SERMs have been linked to a notable reduction in the risk of breast cancer.

Bisphosphonates

This group of drugs is the most frequently prescribed for osteoporosis management, with numerous generic options now available. They are administered in various forms, including daily, weekly, or monthly oral doses, as well as quarterly or yearly intravenous treatments. NICE particularly endorses the use of generic bisphosphonates, with alendronate often recommended as a first-line treatment. However, these may not be suitable or tolerable for everyone. Gastrointestinal discomfort is a common side effect, which can be mitigated by switching to intravenous bisphosphonates or other treatment options. Oral bisphosphonates require careful administration: they should be taken on an empty stomach, 30 to 60 minutes before eating breakfast, and only with plain tap water to ensure proper absorption. It’s important to avoid bisphosphonates in patients with significant renal impairment (chronic kidney disease stages 4/5).

Denosumab

This medication is a fully human monoclonal antibody that targets the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL), which plays a crucial role in the development and activity of osteoclasts. It is authorized for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men who are at a heightened risk of fractures. Denosumab is administered via a subcutaneous injection every six months. One of its advantages is that it does not require dose adjustments for patients with renal impairment.

While bisphosphonates and denosumab are generally beneficial for most patients, two rare but significant adverse events have gained attention. However, it’s crucial to remember that for the vast majority of patients, the advantages of these treatments significantly outweigh the risks.

-

Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: This condition occurs infrequently in patients treated with these medications for osteoporosis. Before starting treatment, especially in patients with additional risk factors like poor oral hygiene, existing dental issues, or glucocorticoid therapy, a dental check-up and preventive dental care are advisable. However, undergoing these treatments should not prevent necessary dental procedures.

-

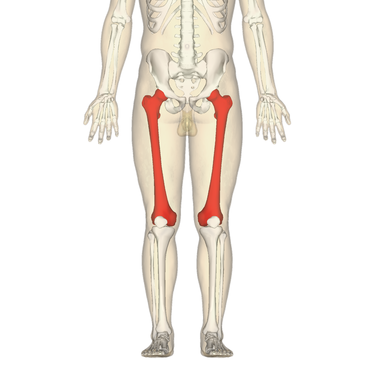

Atypical Femoral Fractures: These unusual fractures, primarily located in the subtrochanteric and diaphyseal areas of the femoral shaft, have been reported. They often occur on both sides, are preceded by pain, and typically heal slowly. Patients undergoing treatment should be informed about reporting any unexpected thigh, groin, or hip pain. If such symptoms arise, a complete femur imaging is recommended. In the event of an atypical fracture, imaging of the other femur is also suggested, along with stopping the treatment and considering alternative therapies. In cases of incomplete fractures, surgical intervention like intramedullary nailing might be advised to prevent the fracture from worsening.

| Femur bones |

|---|

|

Anabolic Approaches

A class of anabolic treatments involves the use of parathyroid hormone peptide known as teriparatide or PTH 1‐34. Initially, these treatments stimulate bone formation, followed by an eventual increase in bone resorption. They show effectiveness in enhancing bone mass and structure, particularly in areas with a dense network of trabeculae, such as the vertebrae. The relatively high cost of these treatments limits their application to patients suffering from severe and progressive osteoporosis, even after undergoing antiresorptive therapy. It’s important to note that the treatment period is restricted to 24 months, and patients need to continue with antiresorptive agents following discontinuation to preserve the gained improvements in bone mass. Additionally, teriparatide is approved for use in men and patients experiencing osteoporosis induced by glucocorticoid use (GIO).

Ongoing Advancements

Researchers are actively exploring alternative therapies for osteoporosis treatment that are currently in the developmental stage. For instance, there is ongoing work on analogs of parathyroid hormone-related peptide, exemplified by abaloparatide . Additionally, investigations are being conducted into inhibitors targeting sclerostin , such as romosozumab , as potential options for addressing osteoporosis.

Alleviating Discomfort and Preventing Falls

Besides the management of pain through analgesia and physical interventions like hydrotherapy or the use of transcutaneous nerve stimulators, certain patients may require evaluation at dedicated pain clinics. Typically, fracture-related pain tends to subside within a span of 6 months, but individuals with vertebral fractures might necessitate long-term pain relief due to ensuing degenerative conditions. Procedures such as vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty may offer valuable options for specific patients experiencing persistent or severe pain arising from recent vertebral fractures.

It is essential to identify factors that increase the risk of falls, such as postural hypotension or drug-induced drowsiness, and take steps to mitigate them whenever feasible. Patients can benefit from physiotherapy interventions designed to enhance their balance and preserve reflexes. The consideration of appropriate walking aids, vision assessments, and the removal of environmental hazards should be part of the overall strategy. In some cases, referral to specialized falls clinics might be a prudent course of action.

Osteomalacia: The Softening of Bones

Osteomalacia, often referred to as ‘softening of bones,’ is characterized by the inadequate mineralization of bone tissue, potentially resulting in symptoms such as bone pain, muscle weakness, and, in some cases, fractures among adults. In children, it can manifest as bone deformities, a condition known as rickets. The leading cause of osteomalacia by a significant margin is a deficiency of vitamin D; however, it’s worth noting that not all individuals with apparent vitamin D deficiency will develop osteomalacia. The highest risk of vitamin D deficiency is associated with individuals who have limited exposure to sunlight, including the frail elderly and those who cover most of their skin with clothing. In these vulnerable groups, the diagnosis should be considered if symptoms are present or if biochemical testing reveals hypocalcaemia, hypophosphataemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, and/or elevated alkaline phosphatase levels.

In cases of deficiency, a regimen of high-dose oral colecalciferol administered over three months (with doses of up to 300,000 IU divided, for example, as 20,000 IU once weekly for 12 weeks) can safely restore most individuals to a replete vitamin D state. For long-term maintenance, individuals may receive combined calcium/vitamin D supplements or low-dose cholecalciferol alone if they are unable to tolerate the combined preparation. In cases of renal failure, active metabolites may be necessary.

Paget’s Bone Condition

Paget’s disease of bone (PDB) impacts approximately 1-2% of individuals aged 55 and above, primarily of Caucasian descent. It is characterized by localized disruptions in bone remodeling, predominantly affecting the axial skeleton, resulting in disorganized bone structure. The pelvis stands as the most frequently affected region, accounting for 70% of cases (as depicted in Figure 11.6), followed by the proximal femur, lumbar spine, skull, and tibia. Complications linked to this condition encompass bone pain, pathological fractures, hearing impairment, nerve compression, and, in rare instances, the development of osteosarcoma. There is growing evidence suggesting that Paget’s disease has a genetic basis, being attributed to various alleles. Mutations in the SQSTM1 gene, which encodes p62, an adaptor protein involved in the NF‐kappa‐B signaling pathway and autophagy, are observed in approximately 10% of patients. Genome-wide association studies have identified seven other loci that increase susceptibility to PDB. It is estimated that the collective influence of these genetic factors accounts for approximately 86% of the population’s risk of developing PDB in patients who do not carry SQSTM1 mutations.

PDB’s activity can be effectively suppressed through bisphosphonate treatment, especially through the use of intravenous zoledronic acid. In many cases, the disease may necessitate treatment only every few years.

Refrences

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) and selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) in cancer treatment

- Paget’s disease of bone: 1877–2023. Etiology, and management of a disease on epidemiologic transition

- Paget’s disease of bone: A rare case in a patient under 40 years of age

- Anabolic Therapy and Optimal Treatment Sequences for Patients With Osteoporosis at High Risk for Fracture

- Comparative efficacy of bone anabolic therapies for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Combination of anabolic and antiresorptive agents for the treatment of osteoporosis

- Emerging Anabolic Treatments for Osteoporosis

- Sclerostin inhibition: A potential new anabolic treatment approach for osteoporosis

- Plumbagin is a NF-κB-inducing kinase inhibitor with dual anabolic and antiresorptive effects that prevents menopausal-related osteoporosis in mice

- Safety and efficacy of sequential treatments for postmenopausal osteoporosis: a network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

- Revisiting hypophosphatemic rickets/osteomalacia

- Abaloparatide: A review of preclinical and clinical studies

- Effects of abaloparatide and teriparatide on bone resorption and bone formation in female mice

- Efficacy of denosumab on bone metabolism and bone mineral density in renal transplant recipients: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Denosumab use in bone fibrous dysplasia refractory to bisphosphonate: A retrospective multicentric study

- Duration of drug holiday of oral bisphosphonate and osteoclast morphology in osteoporosis patients with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw

- The effect of bisphosphonate treatment on osteoclast precursor cells in postmenopausal osteoporosis: The TRIO study

- Osteoclast-Responsive, Injectable Bone of Bisphosphonated-Nanocellulose that Regulates Osteoclast/Osteoblast Activity for Bone Regeneration

- The effects of selective estrogen receptor modulator treatment following hormone replacement therapy on elderly postmenopausal women with osteoporosis

- Osteoporosis risk factors: association with use of hormone replacement therapy and with worry about osteoporosis

- Reasonable osteoporosis prevention: hormone replacement therapy, SERM, or bisphosphonate?

Share

Tags

Counters